‘JIVE TALKIN’: 1975 AND THE BREAKTHROUGH OF DISCO

Few genres of music have taken hold of global popular culture and imagination in the way that disco did in the late 1970s. With its infectious rhythms, lavish orchestration, and lyrics often steeped in escapism, disco dominated radio airwaves, filled dance floors around the world, and shaped the sound of a generation. Songs like Baccara’s ‘Yes Sir, I Can Boogie’ (1978), the Bee Gees’ ‘Stayin’ Alive’ (1977), Gloria Gaynor’s ‘I Will Survive’ (1978), and ABBA’s ‘Dancing Queen’ (1976) were international anthems, becoming instantly recognisable – and danceable – staples of mainstream radio worldwide. In fact, by the end of the 1970s, it was almost impossible to escape either disco or its influence; artists from all genres were incorporating its signature elements, whilst films like Saturday Night Fever (1977) rendered it a cultural phenomenon.

But it was not always this way. As has been the case with most offshoot styles of popular music, the history of disco before it exploded into the mainstream is long and winding.

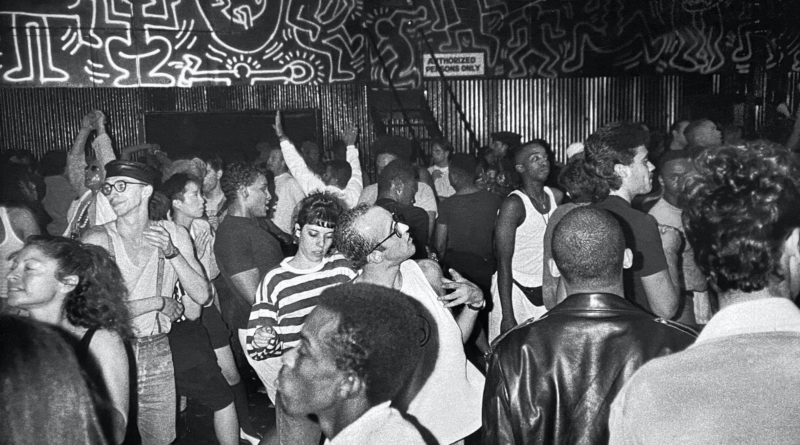

Given its mass appeal, one might assume that the genre emerged from an economically-motivated attempt to make music that would appeal to as many people as possible. The truth, however, could not be further from this. In fact, the genre first took shape in the early 1970s via the underground nightlife scenes in cities like New York, Philadelphia and Chicago. At this early stage, the sound of disco represented not a calculated commercial decision, but rather liberation; it was shaped primarily by Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ communities who had been excluded from the prevailing cultural narrative, and who found that the dance floor offered a space of both belonging and resistance. Venues like The Loft, Paradise Garage (both in New York) and Warehouse (in Chicago) offered a safe space where people of marginalised races, sexualities, and backgrounds could come together and express themselves as they pleased. Releases like Kool and the Gang’s ‘Jungle Boogie’, MFSB’s ‘Love Is the Message’, and Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’, were popular during this period. borrowing from funk’s basslines, soul’s emotional range, Latin percussion, and the steady, hypnotic rhythms of the early electronic experimentation that was occurring simultaneously. The DJs that played these tracks, meanwhile, had just as much influence on this early disco scene as those who had created the records in the first place. Figures like Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles, and Nicky Siano would craft extended mixes and edits of existing tracks to keep the energy upbeat and positive, shaping the tastes and expectations of their club-going audience in the process.

The result was a growing demand for music tailored specifically to the dance floor, something that emerging independent labels like Salsoul, Prelude, and West End would soon begin to capitalise on. Even before their official establishment, the producers and musicians behind these labels were active in shaping the pre-commercial disco sound. Early records — the likes of Joe Bataan’s ‘The Bottle’, First Choice’s ‘Armed and Extremely Dangerous’, and Black Ivory’s ‘Mainline’ — began to lay the groundwork for the instantly recognisable disco sound: a steady four-on-the-floor beat, lush orchestration, syncopated funk-influenced basslines, and emotive, gospel-inflected vocals.

But whilst disco’s presence continued to expand in underground scenes, throughout the early 1970s its presence in the broader music industry remained minimal. Often dubbed disposable or lacking in artistic value by music critics, and with radio stations slow to embrace the genre, disco was dismissed as a fleeting, novelty-tinged trend that was rooted in nightlife as opposed to musicianship. But its popularity on the ground was undeniable, and by the mid-1970s, it began to cross over into the mainstream.

This shift was partly the result of technological developments, with advances in studio recording and sound systems allowing producers and artists to experiment more freely with the layering of instruments and textures. This resulted in a more immersive listening experience that suited a club environment where listeners wanted to lose themselves in the music. The rise of the 12-inch single format was also significant, giving DJs the freedom to mix tracks into longer versions, and in turn keep that four-to-the-floor beat going all through the night.

1975 was a key year for disco in this regard, in that it was at this point that several disco tracks – specifically those including Van McCoy’s ‘The Hustle’ and Silver Convention’s ‘Fly, Robin, Fly’ – began to gain traction outside the club circuit. By the time Isle of Man sibling trio the Bee Gees released their iconic single ‘Jive Talkin’ in May, which became a top 10 hit around the world, the writing was on the wall: disco could no longer be considered music of the underground. Interestingly, ‘Jive Talkin’ marked a radical reinvention for the Bee Gees, who had previously been known for soft rock tunes and ballads. Working with Turkish-American producer Arif Mardin, they embraced a groove-heavy, rhythmic sound that owed far more to funk and soul than their folk-inflected earlier work. The result was a track that made number one in the United States, number five in the UK, and which acted as a key bridge between underground disco and mainstream pop.

Soon, more artists began to catch on to the commercial potential of the disco sound, and what had begun as a relatively slow introduction into the mainstream became more of an explosion. Donna Summer’s ‘Love to Love You Baby’ was another vital track from 1975 in this regard; produced by Giorgio Moroder, the song became a global hit, introducing a sensual, synthesiser-driven edge to disco that increased the genre’s popularity and reach whilst also pointing towards the future of dance music. Also in 1975, Gloria Gaynor’s ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ reached No. 9 on the US charts and was one of the first records to feature a continuous dance mix on its A-side. Meanwhile, tracks like Labelle’s ‘Lady Marmalade’ and The Hues Corporation’s ‘Rock the Boat’ (the latter was originally released in 1974 but peaked in popularity the following year) continued to blur the lines between soul, funk, and disco, helping to further normalize the genre on both radio and television. Elsewhere, artists like Cerrone and Baccara brought a Euro-disco flair to the genre, while ABBA’s blend of big, bold pop melodies and danceable rhythms made them international icons. In America, Nile Rodgers’s band Chic blended tight grooves with a sleek sophistication, winning over both critics and audiences.

By the end of 1975, disco was no longer confined to dance floors in the underground clubs of US cities like New York and Chicago. The genre was everywhere in the charts, on pioneering TV shows like Soul Train, and even seeping into fashion and social trends. Disco artists began to draw interest from major labels, whilst the genre’s unmissable four-to-the-floor groove began to pop up in film and television soundtracks. Combining rhythmic consistency, lush instrumentation, and emotional release, 1975 had revealed disco’s capacity to tap into something universal — something joyous, cathartic, and escapist all at once.

In this sense, 1975 was more than just a successful year for disco – it was the point at which it transitioned from the underground to the mainstream. It also marked the beginning of a cultural shift that would define the second half of the decade, as disco evolved from a subcultural movement into a dominant commercial and creative force that reshaped popular music around the world.

By the end of the 1970s, meanwhile the reach of disco had become almost impossibly vast. Fashions had changed to match the glitz and glamour demanded by the clubs where disco was played. Venues like Studio 54 became cultural landmarks, where celebrities, models, musicians, and fans danced shoulder to shoulder beneath that now iconic sight of a spinning mirrored ball. Saturday Night Fever – the 1977 film starring John Travolta as the disco-obsessed Tony Maneri – defined the genre for the global imagination, with Travolta’s white suit and his attention-attracting dance floor routines becoming instantly recognisable. The soundtrack, featuring multiple Bee Gees hits including ‘Stayin’ Alive’, ‘Night Fever’, ‘More Than A Woman’, ‘You Should Be Dancing’, and of course ‘Jive Talkin’, also became one of the best-selling albums of all time.

And whilst that sight of John Travolta in his white suit will probably continue to remain the most recognisable representation of disco at its peak, it is important to remember where the genre came from: it developed from marginalised spaces where people who were often made to feel unwelcome elsewhere were able to express and enjoy themselves without fear of prejudice. It is amazing to think that what began as a form of resistance and liberation in underground venues actually went on to reshape the sound of popular music, shifting attention away from traditional rock values on a global scale and promoting a kind of popular music that was more rhythmic, emotionally open, and ultimately inclusive.